An Introduction to the Electronic Structure of Atoms and Molecules

Professor of Chemistry / McMaster University / Hamilton, Ontario

An Introduction to the Electronic Structure of Atoms and MoleculesProfessor of Chemistry / McMaster University / Hamilton, Ontario

|

The spatial symmetries of atomic orbitals and the number of each symmetry type are determined by the angular momentum of the electron. The orbitals are in fact labelled by the angular momentum quantum numbers, l and m, which along with the principal quantum number n, completely specify the orbital. Angular momentum plays a similar role in determining the symmetries and number of orbitals of each symmetry species in the molecular case.

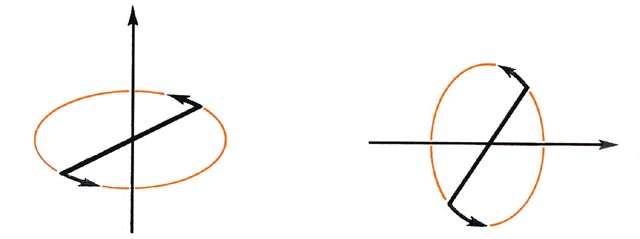

In an atom all of the angular momentum is electronic in origin. In the molecular case, the molecule as a whole rotates in space and the nuclei contribute to the total angular momentum of the system. The nuclei and the electrons of a diatomic molecule can rotate about both of the axes which are perpendicular to the bond axis (Fig. 8-1).

In a classical analogue the electrons and the nuclei exchange angular momentum during these rotations and the angular momentum of the electrons is not separately conserved. Thus the magnitude of the total electronic angular momentum in a diatomic molecule, unlike the atomic case, is not quantized. Instead, the magnitude of the total angular momentum, nuclei and electrons, is quantized. Only the electrons, however, may rotate about the internuclear axis and this component of the angular momentum is entirely electronic in origin. As long as the molecule is left undisturbed, this one component of the angular momentum remains fixed in value and its magnitude, is, therefore, quantized.

The angular momentum vector for rotation

about the bond will lie along the bond axis. This vector represents the

component of the total angular momentum vector along the internuclear axis.

As in the atomic case, quantum mechanics restricts the values of the component

of the total angular momentum vector along a given axis to integral multiples

of (h/2p). The quantum number in this

case is denoted by the Greek letter l (lambda).

It is analogous to the quantum number m in the atomic case. The

possible values for l are

|

|

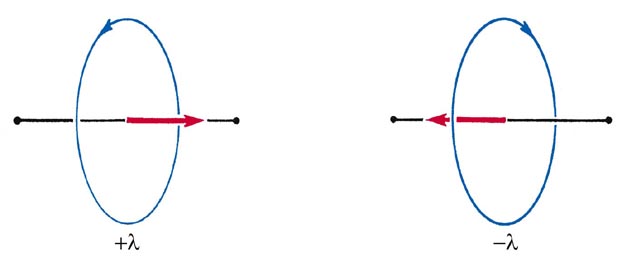

Since the rotation may occur in the clockwise or anticlockwise sense about the axis, the angular momentum vector component may be pointed in either direction along the bond (Fig. 8-2).

Fig. 8-2. The two directions for the orbital angular momentum vector l for the rotation of an electron about the internuclear axis of a diatomic molecule.

Correspondingly, the allowed values of the angular momentum about the internuclear axis are 0, ±1 (h/2p), ±2(h/2p), etc., or in general, ±l(h/2p). Thus when l is different from zero, each energy level is doubly degenerate corresponding to the two possible directions for the component l along the bond axis.

The molecular orbitals are labelled according to the values of the quantum number l. When l = 0, they are called s orbitals; when l = 1, p orbitals; when l = 2, d orbitals, etc. This is analogous to the labelling of the atomic orbitals as s, p, d, . . . , as determined by their l value.

We know less about the angular momentum of an electron

in a diatomic molecule than in an atom. In the atomic case it is possible

to determine the magnitude of the total angular momentum, as given by the

quantum number l, and the magnitude of one of its components, as

given by the quantum number m. In a linear molecule our knowledge

is more restricted and we are limited to a single quantum number l,

which determines only the component of angular momentum about the bond

axis.

|

|

|

|